Finding resilience is a lifelong journey

By

—

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2017, click here.

Bouncing back.

How do you recover from a setback?

It’s an age-old question that the Arizona State University community is pondering in innovative ways, looking at resilience from the perspective of research, health and the arts — and personally as well. What are the strategies that people use to get through adversity over many years, or day to day, or even hour to hour?

Last spring, ASU started a new initiative, the Center for Mindfulness, Compassion and Resilience, which will connect researchers, practitioners and scholars across disciplines at ASU in the study of well-being. Teri Pipe, ASU's chief well-being officer, said mindfullness is a skill that “will help all of us cope much better as a society.”

“Each of us face adversity in life. Resilience is the human capacity not only to 'bounce back' from life's slings and arrows, but also to become stronger and more capable of facing the next challenge,” she said. “The connection with mindfulness is that we must be alert to the opportunity to learn and grow through the experience. We have much to learn from individuals and cultures that have faced adversity; thus resilience is not only an individual capacity, but also a societal one.”

Under Pipe's leadership, the center focuses on deepening ASU's culture of healthfulness, personal balance and resiliency among students and employees.

Here are some other ways that ASU is reflecting on the concept of resilience:

The research

Frank Infurna, an assistant professor of psychology at ASU, is interested in how people develop and change over time as a result of adversity.

“How do individuals grow as a function of various life events or adversities, such as chronic illness or unemployment or bereavement? What are the resources and strategies they use?” asked Infurna, who is a developmental psychologist.

He has found that resilience is social.

“The individual’s ability to have relationships, a good social network in place, has been the strongest predictor of whether someone is able to overcome adversity,” he said.

Infurna received a $3.4 million grant from the Templeton Foundation last year and together with ASU colleagues Suniya S. Luthar and Kevin Grimm is now working on a new research project looking at the nuances of resilience in midlife. They will follow people age 50 to 65 for two years, giving them monthly questionnaires that assess different aspects of their lives — physical health, mental health, quality of social relationships, as well as character strengths such as empathy and gratitude.

They’ll also record life events: whether they were fired, had a major disagreement with a family member, become a caregiver.

“A lot of the research within resilience follows people every three to six months or year to year. With that time frame, you lose detail in terms of the immediate changes that occur,” Infurna said. “Our primary aim is to look at the nature of the changes and what are the factors that predict better outcomes? When something bad happens, what or who are they relying on to overcome this?”

So far, the project has recruited 280 adults, with a goal of 350.

Infurna said his team is challenging the research that says resilience is the norm.

“I think under that is a lot of variability in terms of how individuals respond to adversity and that it’s OK to struggle for a period of time after something traumatic happens,” he said.

“We’re trying to adjust this cultural narrative, in the U.S., of what it means to be resilient.”

The creatives

Navigating setbacks is especially relevant to artists, so this term, the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts offered a class called “Failure, Design and the Arts.”

“They’re critiqued all the time. They’re critiqued in public. Nine out of 10 times they won’t get a call back from an audition,” said Megan Workmon, the manager of student engagement for the institute, who is co-teaching the course with William Heywood, assistant director of the Design School, assistant clinical professor in the Department of Visual Communication and a clinical psychologist. Both have creative backgrounds — Workmon as an opera singer and Heywood as a photographer.

“With critique, what you produce is so tied up with your identity that it’s hard to divorce yourself, as the creative person, from your individual identity. Failure seems very personal,” she said.

Workmon and Heywood created a one-credit course that’s being offered for the first time as a 300-level elective. The 20 students span all disciplines within Herberger.

Each class session begins with a period of mindfulness.

“In class, we had a conversation about critique and how you get ‘unstuck.’ A lot of them talked about how they bottled up their emotions but it came out another time. Mindfulness is a way to check in with how you’re truly feeling about things as they’re occurring,” she said.

The course covered the “inner voice of judgment” and, a few weeks later, “the inner voice of persistence.”

“If you want to replace that voice that tells you you’re not good enough with something that will tell you you’re going to make it through no matter what, then what does it look like?” Workmon said.

The class projects are art-based, and students work in whatever medium they feel most comfortable — poetry, illustration, essays, video. For the project on the “inner voice of judgment,” a dance student did the same movements over and over to symbolize repetition.

The students answered a questionnaire at the beginning of the class and will take one at the end as well. Workmon will measure their self-efficacy, mind-set, grit and persistence, then use the results for her dissertation. She is a doctoral student in educational leadership and innovation in the Mary Lou Fulton Teacher’s College.

“Mind-set” is a continuum from “fixed” (the belief that our characters can’t be changed) to “growth” (the belief that we can learn and overcome struggles). The duality is particularly interesting for artists, she said.

“Part of fixed mind-set is talent, and growth mind-set is hard work — and in their fields, talent and hard work are equally valued.”

The final component of the class, which Workmon hopes to offer again in the spring, is a reflection. The students must do that project in a medium that makes them uncomfortable.

“Do something risky. That can give you an opportunity to interrupt those negative thoughts,” she said.

The personal journey

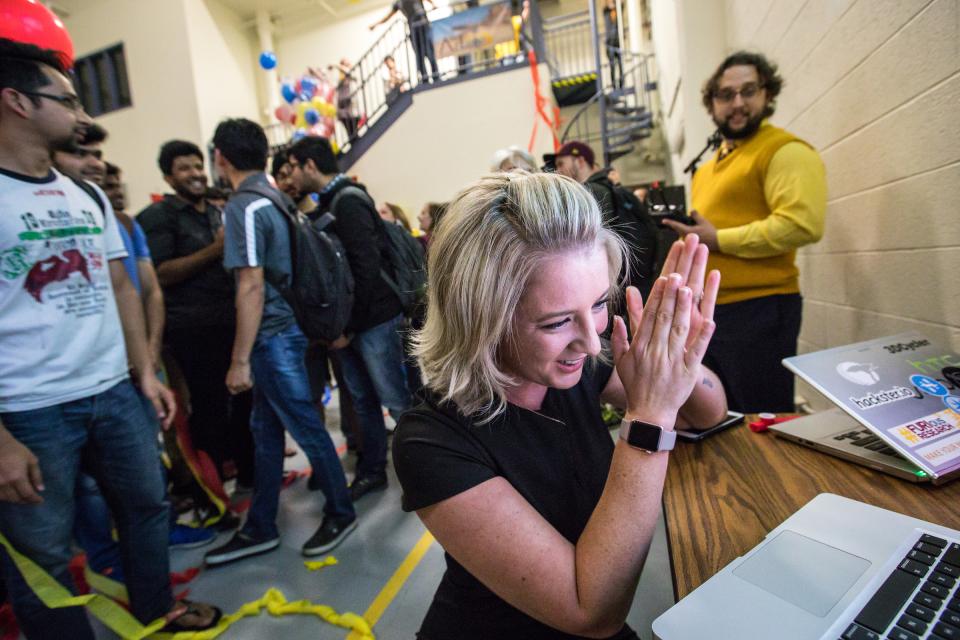

Lynne Nethken led a team of Arizona students in the AZLoop project — a high-speed, futuristic transportation system — that garnered international attention at Elon Musk’s SpaceX Hyperloop Competition recently.

But her journey to engineering success was anything but fast, and it required an enormous amount of persistence and grit.

Nethken went to a poor inner-city high school in Memphis, where physics wasn’t even offered. After graduating, she enrolled at Memphis State, majoring in business.

“I made an attempt. It went poorly. I was not interested in my classes. I dropped out,” she said.

She worked in some retail jobs, moved to Colorado and, in her early 20s, decided to give college another try.

“I said, ‘I have to have this piece of paper.’ So I went right back into business, and, no surprise, I dropped out again,” she said.

“It was lot of trial and error. A lot of really rough patches. There were some low times. There were times I was flat broke and I had nothing.”

She found a job in health administration that paid well but wasn’t challenging. It did give her time to explore her interests, and she realized she was always fascinated by space exploration, which she mentioned to a few people.

“Nobody understood. I didn’t have a lot of support or any sort of encouragement to do that.”

Finally, in 2010 she decided to sell everything she owned, move to Arizona and pursue an engineering degree at ASU. Although her mother lived in Phoenix, the move still was terrifying.

She started classes at Scottsdale Community College, where calculus was a struggle.

“I didn’t go to good schools, and I had a poor math background,” she said. “Math scared me, but it really was about how hard are you willing to work to learn it?”

Community college is where she began to develop her power to focus on her studies, and she transferred to ASU’s Polytechnic campus.

“I had classes I was interested in, and it was like nothing else mattered. I saw this light at the end of the tunnel,” she said.

At Poly, she found the support she needed from her professors.

“I was able to build relationships there to where if I was struggling with something, they could talk sense into me and encourage me,” she said.

Nethken earned her bachelor of science degree in engineering in 2016, and now, at age 33, is in graduate school in the School for Engineering of Matter, Transport and Energy. She hopes to pursue a doctorate.

“I had to have a crazy level of determination and to struggle along this path for 10 years before I really figured it out and said, ‘I can do this,’ ” she said.

“I think my definition of resilience is if you fail or a hit a roadblock, how hard are you willing to work to get around it? If you have determination, nothing will stop you.”

Learn more

- The Center for Mindfulness, Compassion and Resilience is hosting a “Mindfulness in the Park” event from 5:30-7 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 26, in Civic Space Park in downtown Phoenix. The event is free and open to the public. Find details here.

- A free workshop on stress and resilience will be offered by Leadership and Workforce Development for faculty and staff from 8:30 to 10:30 a.m. Wednesday, Oct. 4, on the Tempe campus. Find details here.