Virtual patient could help veterans with insomnia

By

—

Could a virtual insomnia patient help real-life veterans with their sleep disorders?

That’s what Thomas Parsons wants to find out.

Parsons, a Grace Center Professor for Innovation in Clinical Education, Simulation Science and Immersive Technology at Arizona State University’s Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, was recently awarded a $5.2 million, four-year grant from the Department of Defense to develop virtual standardized insomnia patients.

The need is clear. According to a 2021 study by the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, insomnia diagnoses increased 45-fold among U.S. service members from 2015–19.

The other problem: Parsons said there are not enough therapists trained specifically to help veterans suffering from insomnia. Thus, the virtual insomnia patient, if effective, could reduce the need for paid actors or “practice patients” and create a higher consistency of care.

ASU News talked to Parsons about his project.

Note: The interview has been edited lightly for brevity and clarity.

Question: Why did you apply for this specific grant?

Answer: I’m a veteran (Air Force), and a big part of this is to help military service members and veterans who had combat stress symptoms, like a blast injury, and now they just can’t sleep. I’m also a psychologist, and a big part of this is we can kind of help train psychologists a little bit better in this sort of intervention. So, those were the two biggest reasons.

Q: Just how big of a problem is insomnia among military members?

A: It’s a really big issue. And the problem is, it just kind of amplifies all these other issues that they’re struggling with. Also, a lot of time in the military, as part of your training, you have to get used to not having sleep for certain periods of time. Then you have all the combat stress symptoms, so when they do sleep, they end up having nightmares. When they first get back, it’s great because their family and friends are there for them.

But after a couple of weeks, after a month, people have to work, they go back to their lives, and a lot of the problems start settling in. That’s compounded by the fact a lot of people in psychiatry and psychology are not trained to deal with insomnia. So, they’re back, their support system is basically dispersed, and they have a hard time finding somebody to help them.

Q: Is that because most patients with sleep disorders end up at a sleep clinic?

A: Right. Most PhD programs, psychiatry programs and psychiatric nurses are just not trained how to do cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. That’s a big issue.

Q: So, how would a virtual patient help?

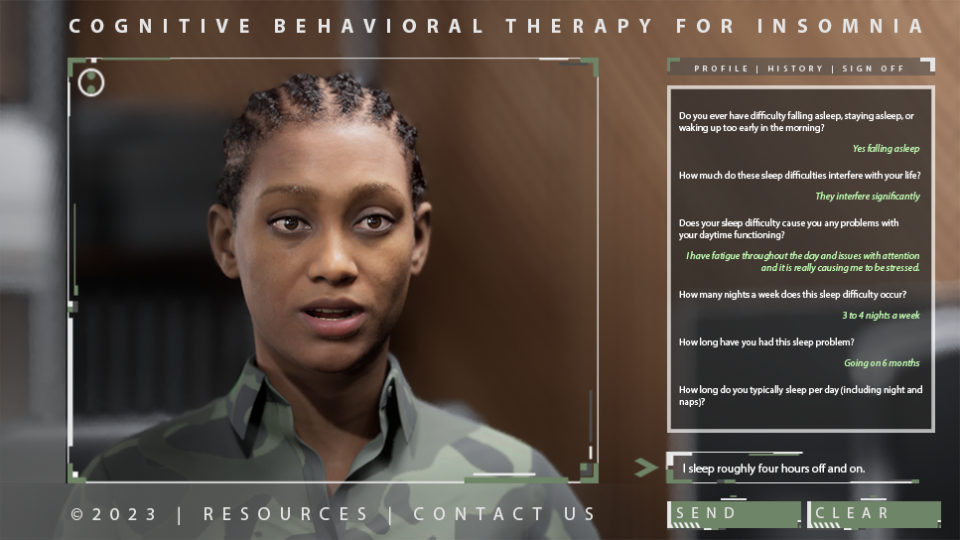

A: Well, there’s a bit of a twist on this because we’re not going to work directly with the patients or the military service members. This is to train therapists. We have video of military service members or veterans going through therapy, and we have that for different ethnicities, different genders, different ages. So, we take the transcripts of the things we said, how did they say it, what did they look like and then there’s the virtual standardized agent.

So, the things that real humans have said in the past, the patients, are fed into the virtual patient. The way it works is a messaging system. The machine listens for certain keywords that are asked by the therapist, and then it says back the same sorts of things that people in life have said. And that helps the therapist learn how to treat military members.

Computer-generated patients interact with therapists based on recordings from human patients. Image courtesy Thomas Parsons

Q: Are there other potential uses for a virtual patient?

A: There’s so many that my brain just keeps swimming with possibilities. But first, we want to have this out there as a proven trainer that can be used in conjunction with other training. One of the things that I’m really interested in is suicide. That’s going to be at the tail end of this grant. In August I’m going to Washington, D.C., and I’m going to be talking about all these veterans who are committing suicide and they don’t know why.

Q: So, if this works for military members with insomnia, it could be used to help therapists work with veterans who are considering suicide?

A: Absolutely. That’s a big part of this.

Top photo from iStock/Getty images